Grefen-Peters, Silke

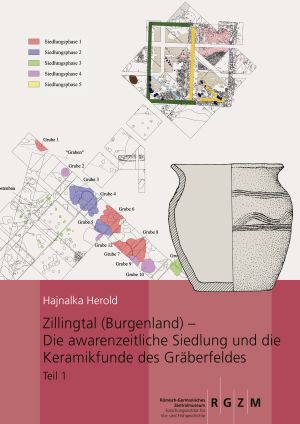

Zillingtal (Burgenland) – Die awarenzeitliche Siedlung und die Keramikfunde des Gräberfeldes: Teil 1

The study of the early medieval settlement (7th-8th century AD) and the pottery finds from the associated cemetery focuses on three main areas: Avar settlement features and settlement structures in the Carpathian Basin, pottery production and use in the Avar period, and Avar traditions in the Zillingtal regarding the burial of pottery vessels.

Among the settlement finds, the early medieval reuse of the Roman ruins is of particular interest. The analysis of the find material focuses on the pottery finds, together with the pottery vessels from the Avar cemetery. Archaeological and archaeometric analyses as well as methods of experimental archaeology are used. The chronology of the pottery and the anthropological data of the burials form the basis for the analysis of Avar traditions in the burial of pottery.

Part 2 here.

Das merowingerzeitliche Gräberfeld von Dortmund-Asseln

Early medieval cemeteries are rare in Westphalia, even more so in the Ruhr area. Therefore, it was particularly gratifying that in Dortmund-Asseln, during a systematic excavation, fourteen female and ten male individuals could be examined in predominantly undisturbed and, by Westphalian standards, well preserved and excellently equipped inhumation graves. In addition, a horse grave and a dog grave were unearthed. Despite the most difficult soil conditions, the excavator Bernhard Sicherl achieved a maximum of information about the archaeological features, which – combined with the rich find material – provide an excellent basis for the analysis of the graves. The cemetery of Dortmund-Asseln is of particular importance, because models for conceivable social structures could be worked out here on a small scale, which can also contribute to the understanding of ways of life in other places in the Merovingian Period.

Die Burg Marmels: Eine bündnerische Balmburg im Spiegel von Archäologie und Geschichte

The ruins of Marmels Castle are located some one hundred metres above the Marmorera reservoir, below a massive ledge (municipality of Marmorera situated in the Oberhalbstein/Sursés Valley in Canton Grisons). In the High and Late Middle Ages, the castle was in the hands of the Lords of Marmels, who were ministerials of the Bishop of Chur. The complex at this dizzy height once included a chapel with two adjacent buildings, a gateway building and a representative residential tower with at least four storeys.

As part of a comprehensive restoration of the castle ruins the Archaeological Services of Canton Grisons were able to carry out architectural surveying of the preserved building remains and excavations in the grounds in 1987 and 1988. An excavation being carried out in castle grounds is a rare occurrence in Canton Grisons. However, it was actually the findings from the excavations that were of particular significance for Swiss castle research.

Thanks to the location of the castle beneath a massive ledge, large parts of the complex had at all times been protected from the elements – a stroke of luck for researchers, since the finds were deposited in mostly dry conditions over the centuries. Apart from their large number, the variety and state of preservation of the finds was also extraordinary. Particularly the organic finds, which in medieval excavations usually only occur in small numbers, were numerous in Marmels: some 1,000 fragments of wood including utensils, furniture parts, architectural timbers and building waste were found in the excavated layers. Other finds included leather fragments and shoes, remnants of parchment, some of which bore writing, more than 21,000 animal bones and 18,000 individual plant remains. Besides the organic finds, the excavations also unearthed metal implements and innumerable fragments of slag, which attested to the production and working of metal, some pottery shards and a large assemblage of steatite vessels. Various wooden objects (architectural timbers and implements) yielded absolute dates by dendrochronological means.

This allowed us to date the construction of the castle to 1140 and its abandonment to the late 14th or early 15th century. Certain events from the castle’s history could also be dated using this method.