Heher, Dominik

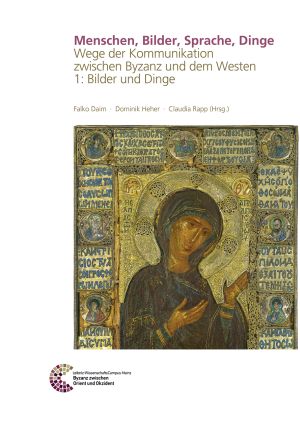

Menschen, Bilder, Sprache, Dinge: Wege der Kommunikation zwischen Byzanz und dem Westen 1: Bilder und Dinge

In 2018, the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz presents in cooperation with the Schallaburg, the splendid Renaissance castle near Melk (Lower Austria), the exhibition »Byzantium & the West: 1000 forgotten years «.

Both Byzantium and the European West spring from the Roman Empire, but as early as Late Antiquity experience different developments. While the Roman Empire continued to exist in the East and passed seamlessly into the Byzantine Empire of the Middle Ages, pagan polities took its place in the West: the kingdoms of the Goths, Vandals, Anglo-Saxons, Lombards and Franks. Although Byzantium was respected or accepted as a major power by the other European entities for at least 800 years, territorial conflicts, disputes, and cultural differences quickly emerged. In addition, communication became increasingly difficult - in the "orthodox" East, Greek was the common language, while in the "Catholic" West, Latin was the lingua franca. Differences in liturgy and questions of belief intensified the disparities or were even (religio-) politically underlined to emphasize dissimilarity. But one still continued to admire "wealthy Constantinople" and the Byzantine treasures - among them the magnificent silks, ivory reliefs, technical marvels, plentiful relics and magnificent buildings.

The change came in 1204 with the conquest and plunder of Constantinople by the Crusaders. For the already weakened Byzantine Empire, this catastrophe meant a completely new situation as an empire in exile, whose emperor and patriarch had to flee to Asia Minor. Across much of the former European Byzantine Empire, crusader states spread; Venice and Genoa, which had previously been strongly present as trade powers under special treaties, became major determinants of the western powers in the East.

On the occasion of this exhibition, two accompanying volumes with a total of 41 contributions concerning the varied and changing relationships between the Latin West and the Byzantine Empire are being published. The volumes are structured according to the media of communication: people, images, language and things. They collect contributions from renowned scientists with archaeological, art historical, philological and historical priorities. Several overviews and detailed studies are drawn from research projects of the Leibniz- ScienceCampus Mainz: Byzantium between Orient and Occident, as well as the focus on Byzantine and medieval research of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna.

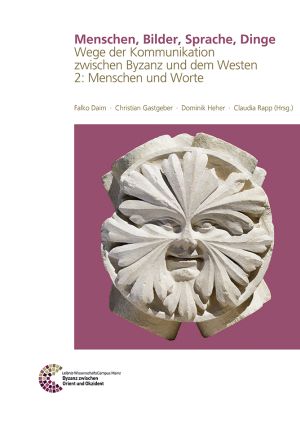

Menschen, Bilder, Sprache, Dinge: Wege der Kommunikation zwischen Byzanz und dem Westen 2: Menschen und Worte

In 2018, the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz presents in cooperation with the Schallaburg, the splendid Renaissance castle near Melk (Lower Austria), the exhibition »Byzantium & the West: 1000 forgotten years «.

Both Byzantium and the European West spring from the Roman Empire, but as early as Late Antiquity experience different developments. While the Roman Empire continued to exist in the East and passed seamlessly into the Byzantine Empire of the Middle Ages, pagan took its place in the West: the kingdoms of the Goths, Vandals, Anglo-Saxons, Lombards and Franks. Although Byzantium was respected or accepted as a major power by the other European entities for at least 800 years, territorial conflicts, disputes, and cultural differences quickly emerged. In addition, communication became increasingly difficult - in the "orthodox" East, Greek was the common language, while in the "Catholic" West, Latin was the lingua franca. Differences in liturgy and questions of belief intensified the disparities or were even (religio-) politically underlined to emphasize dissimilarity. But one still continued to admire "wealthy Constantinople" and the Byzantine treasures - among them the magnificent silks, ivory reliefs, technical marvels, plentiful relics and magnificent buildings.

The change came in 1204 with the conquest and plunder of Constantinople by the Crusaders. For the already weakened Byzantine Empire, this catastrophe meant a completely new situation as an empire in exile, whose emperor and patriarch had to flee to Asia Minor. Across much of the former European Byzantine Empire, crusader states spread; Venice and Genoa, which had previously been strongly present as trade powers under special treaties, became major determinants of the western powers in the East.

On the occasion of this exhibition, two accompanying volumes with a total of 41 contributions concerning the varied and changing relationships between the Latin West and the Byzantine Empire are being published. The volumes are structured according to the media of communication: people, images, language and things. They collect contributions from renowned scientists with archaeological, art historical, philological and historical priorities. Several overviews and detailed studies are drawn from research projects of the Leibniz- ScienceCampus Mainz: Byzantium between Orient and Occident, as well as the focus on Byzantine and medieval research of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna.

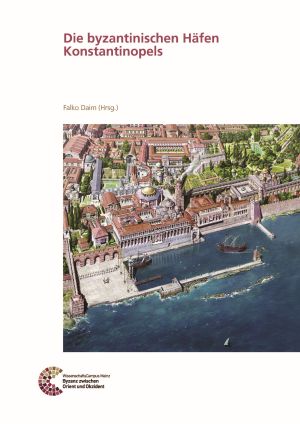

Die byzantinischen Häfen Konstantinopels

The fortunes of Byzantine Constantinople always have been intrinsically tied to the sea. Topographical, demographical and economical development of the city is reflected in the history of its harbours, which for the first time is concerned in its entirety in this volume.

Twelve studies regarding the harbours and landing places of the city at the Sea of Marmara and the Golden Horn – but as well regarding those in their European as in their Asian surroundings – are creating a synthesis of the current state of research by analysis of written, pictorial and archaeological sources.

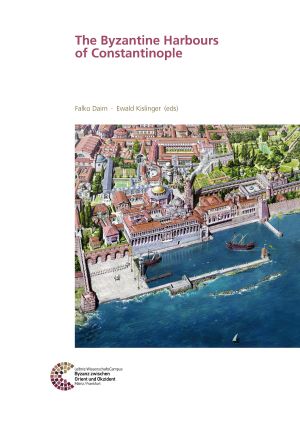

The Byzantine Harbours of Constantinople

The fortunes of Byzantine Constantinople have always been inextricably linked to the sea. The topographical, demographic and economic development of the city and its networks are reflected in the history of its harbours. This volume offers an exhaustive study of Constantinople’s Byzantine harbours on the Sea of Marmara and the Golden Horn, as well as nearby European and Asian landing stages. The fifteen chapters by eleven contributors here present a broad synthesis of the current state of research using written, pictorial and archaeological sources.